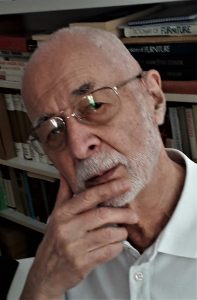

Aleksandar Ajzinberg, redovni professor Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu, rođen je 13.05.1930. godine u Beogradu.

Aleksandar Ajzinberg, redovni professor Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu, rođen je 13.05.1930. godine u Beogradu.

U vreme nemačke opupacije 1941. godine, zajedno sa roditeljima je uhapšen od strane kvislinških vlasti a početkom 1942, pred deportaciju u logor na Sajmištu, sa majkom je pobegao iz zatvora. Rat je, zajedno sa majkom, proveo u Homoljskim planinama skrivajući svoje poreklo. Njegov otac ubijen je u logoru na Sajmištu. Po završetku Drugog svetskog rata bio je dva puta zatvaran (1945. i 1947.) zbog sumnje novih vlasti da je bio saradnik okupatora.

Diplomirao je na Arhitektonskom odseku Akademije primenjenih umetnosti u Beogradu 1955. godine. Bavio se dizajnom i projektovanjem enterijera stambenih i javnih objekata, a od 1982 do odlaska u penziju 1995. bio je professor na odseku enterijera Fakulteta primenjenih umetnosti u Beogradu. Od 2001. Do 2006. predavao je na Odseku enterijera Akademije lepih umetnosti u Beogradu. Autor je nekoliko knjiga umetnosti (Stilska unutrašnja arhitektura — od praistorije do Baroka, Univerzitet umetnosti u Beogradu 1994; Terminoloski recnik STILOVI, Prosveta, Beograd, 2007 ; STILOVI — od praistorije do Secesije, Građevinska Knjiga,Beograd, 2010)

Na Književnim konkursima Saveza jevrejskih opština Jugoslavije (SCG) dobio je nekoliko nagrada:

1995. – 13 Pisama (I nagrada),

1999. – Najzad sloboda! (II nagrada),

2004. – Poslednji let (III nagrada),

2005. – Čekanja (III nagrada).

Oženjen je, ima sina, unuka i dve unuke koji žive u Izraelu. Živi i radi u Beogradu.

Za učesnike BEOgradske avanTURE odgovorio je na pitanja vezana za događaje iz njegovog ličnog života.

Aleksandar Ajzinberg sa prof. Majom Keskinov i učenicima na promociji knjige 2014. godine

Kada je rat počeo, bili ste jako mladi. Koliko je teško bilo da dete Vaših godina procesuira i

prihvati sva zla koje rat donosi?

Kad je rat počeo nisam bio svestan koliko će da traje i kakva će zla da donese. Sečajući se onog što

sam doživeo prvih meseci okupacije naše zemlje, sada posle osamdeset godina, mislim da je to tada za

mene bilo nešto kao da gledam neki film koji će uskoro da se završi.

- Koliko je rat uticao na izgradnju Vaše ličnosti i pogleda na svet?

Nisam razmišljao o tome da li je rat uticao na razvoj moje ličnosti i pogleda na svet ali, sada posle

ovog pitanja i razmišljanja o njemu, verujem da je veoma uticao na izgradnju moje ličnosti. Mislim

da sam postao svestan da život zahteva borbu, da uspeh ne dolazi sam od sebe, da treba verovati

ljudima jer ima mnogo dobrih, ali da uvek možemo naići i na nekog ko će se ponašati tako da naša

ličnost i pa čak i naš život budu ugoženi. Ipak, ne treba očekivati da će važne stvari neko drugi uraditi

umesto nas. Uspesi se postižu jedino radom i borbom.

- Kako ste se osetili kada ste se još kao dete doživeli da budete drugačije tretirani samo zbog

pripadnosti drugoj veroispovesti?

Ja nisam bio nimalo religiozan. Bio sam isuviše mali da bih razmišljao o tome da sam i zašto sam

drugačije tretiran jer u mom najranijem detinjstvu toga nije bilo, iako je u nekim mojim

dokumentima pisalo da pripadam drugoj veroispovesti. Kad je izbio rat znao sam da je došlo vreme

da budem proganjan, jer nemački okupatori proganjaju one za koje negde piše da su Jevreji, a da

neki koji zdušno služe Nemcima ( a to su bili Ljotićevci, srpska policija i Pećančevi četnici), čine to još

žešće od Nemaca. Kad govorim o proganjanju, znao sam da hapse, vode u zatvor, maltretiraju, a

ponekad i streljaju po sto ljudi za svakog ubijenog nemačkog vojnika. Tek više meseci po završetku

rata sam saznao šta se sa onima koji su odvedeni u zatvor dešavalo. Istina, nisu ni odrasli znali sve o

koncentracionim logorima, gasnim komorama i kamionima i krematorijima.

- Nakon toliko proživljenog i toliko iskustva, kakvo Vam je sada gledište na rat uopšteno?

Nažalost, svestan sam da će, dokle god bude bilo ljudskog roda, biti međusobnog ubijanja i ratova.

- Da li se uprkos svim nedaćama koju su obeležile Vaše detinjstvo i dalje sećate lepih trenutaka iz

detinjstva?

Pamćenje mi sada, u mojoj devedeset i drugoj godini, popušta. Ne sećam se mnogo lepih trenutaka iz

detinjstva. Pamtim neke trenutke iz osnovne škole i odlazaka na letovanje, pamtim oca, prabaku u

Zemunu, kuće u Budimpešti gde je stanovala jedna moja baba-tetka, sećam se nekih trenutaka iz

zoološkog vrta na Kalemegdanu, klizanja na Kalemegdanu, igranja šaha sa jednim mojim školskim

drugom i odlazaka na dorćolsku obalu Dunava gde sam, sa susedima (pet ili šest godina starijim od

mene) puštao modele aviona.

- Vaš otac bio je zatvoren u logoru, dok ste Vi sa svojom majkom pokušavali da pobegnete. Šta Vam

je davalo snage da se borite?

Sećam se sveštenikove ponude i znam da je moj otac nije prihvatio samo zato što nije želeo da učini

nešto što bi bilo kao neka predaja okupatoru. Danas sam svestan da bi se, iako bi mi bili pokršteni,

uvek našao neki „cinkaroš“ koji bi dojavio vlastima da se pod srpaskim prezimenom i krštenicom

Pravoslavne crkve kriju Jevreji i da bismo svi bili pohapšeni i pobijeni.

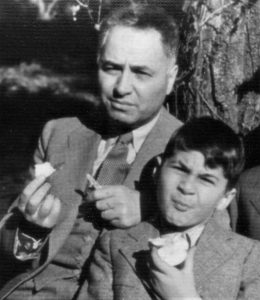

Aleksandar sa ocem Matvejem, oko 1937.g.

- Sa čime Vam je bilo najteže da se suočite tada?

Nisam svestan da mi je za sve ono vreme bilo teško. Naprotiv, svaki događaj kada sam sa majkom

uspeo da izbegnem neku opasnost, dođem do nešto hrane ili odeće činio me je srećnim. Glad,

opasnosti, zima, nedostatak odeće i obuće, iako stalno prisutni, nisu mi se činili kao neka teškoća.

- U jednom pismu navodite da je pravoslavni sveštenik ponudio Vašem ocu da se pokrstite, kako

biste izbegli nevolje koje su tada pogađale Jevreje, a on je to odbio. Da li danas smatrate da je to

moglo da promeni ishod vaše situacije?

Sećam se sveštenikove ponude i znam da je moj otac nije prihvatio samo zato što nije želeo da učini

nešto što bi bilo kao neka predaja okupatoru. Danas sam svestan da bi se, iako bi mi bili pokršteni,

uvek našao neki „cinkaroš“ koji bi dojavio vlastima da se pod srpaskim prezimenom i krštenicom

Pravoslavne crkve kriju Jevreji i da bismo svi bili pohapšeni i pobijeni.

Aleksandar pred polazak u gimnaziju, 1940.g.

- Na koji način je gubitak oca u ranim godinama i na tako svirep način, uticao na Vaš kasniji život?

Toga je sigurno bilo ali kada i kako je to uticalo, ali ne znam … Oca neizmerno žalim ali nisam svestan

na koji način je njegov gubitak uticao na moj kasniji život.

- U knjizi spominjete dosta ljudi i porodica koje su tokom rata pokušale da Vam pomognu. Da li

Vas je rat zbližio sa nekim ljudima i kome ste najviše zahvalni?

Ima mnogo ljudi koji su mojoj majci i meni pomogli ili pokušali da pomognu. O njihovoj pomoći pred

begstvo iz Sopota i za vreme skrivanja u Beogradu, pisao sam u knjizi Pisma Matveju. O pomoći

četnika Draže Mihajlovića i divnih homoljskih seljaka nisam dovoljno pisao niti mogu dovoljno da

napišem. Po završetku rata sa četnicima nisam imao nikave veze, a sa homoljcima dugo nisam smeo

da se viđam ili dopisujem jer bi UDBA ili OZNA to saznala i okrivila me za nekakvu nenarodnu

delatnost. Trebalo je da prođe trideset i pet godina da bi se vremena promenila, ja odlučio da odem u

te krajeve i vidim sa ljudima koji su mojoj majci i meni pomogli da preživimo. Taj odlazak sam

opisao u priči POSLE TRIDESET PET GODINA .

Sada se ponekad viđem sa unucima i praunucima onih kod kojih smo se neko vreme krli, a u vezi sam

i sa Slavijankom onom bebom kojoj sam sekao pupak… Sa ponekima sam u elektronskoj vezi.

- Odrasli ste u Beogradu, a po zanimanju ste arhitekta. Koliko se izgled Beograda razlikuje u

odnosu na doba u kom ste Vi odrasli, i da li Vam se više dopada kakav je bio tada ili kakav je danas?

Kao što ste iz knjige mogli videti mi se u našu kuću na Gundulićevom Vencu 53 (90 m2) nismo mogli

vratiti. Za vreme okupacije tu se uselio drugi narod, a po završetku rata komunisti su nam to

definitivno onemogućili. Živeli smo sa mojom bakom, tetkom Ernom i Mihajlom na Pašinom Brdu

koje je, u ono vreme bilo na drugom kraju sveta. Kao dete, dobro se sećam Dorćola gde smo živeli, a

Vračar sam „upoznao“ tek posle rata. Koliko se taj deo grada pomenio teško mi je reći, ali mislim da

je mnoštvo novih velikih zgrada, kao i u drugim delovima Beograda, učinio da nestanu lepi

dobrosusedski odnosi i da su doveli do izvesne otuđenosti među ljudima. O razlici u izgledu ne bih

mogao ništa reći jer bi mi to, kao arhitekti zahtevalo komparaciju prostora, mnogih detalja i niza

stvari koje mi nisu dostupne.

Aleksandar sa majkom Gretom na ulici, oko 1937. i 10 godina kasnije

- U Beogradu živite i dan-danas. Da li postoji poseban razlog što ste tu ostali i nakon svih nemilih

događaja koji su Vam se ovde dogodili?

Radovao me je povratak u Beograd iz puno razloga, iako to vraćanje u tada novi komunistički

ambijent nije bio nimalo prijatan. Nekoliko godina kasnije moja majka i ja smo razmišljali o odlasku

nekud gde bi se moglo „normalno živeti“ i raditi brz pritisaka nove vlasti. To tada nije bilo moguće.

Vlasti nisu dozvoljavale odlazak iz zemlje. Kasnje, kada je bilo lakše otići u inostranstvo, ja sam

studirao, diplomirao, zaposlio se i radio, pa se želja za odlaskom smanjila. Oženio sam se, u sretnom

braku sam sa suprugom već 60 godina, lepo se slažemo, imamo sina, unuka i dve unuke koji žive u

inostranstvu i nemamo razloga za napuštanje ovog grada bez obzira na sve što se u našoj zemlji

dešava.

- Koliko Vam je važno da se sva sećanja na događaje iz rata sačuvaju od zaborava? Da li je to bio

jedan od razloga da objavite ova, isprva privatna pisma?

Do objavljivanja mojih privatnih pisama u knjizi PISMA MATVEJU došlo je na insistiranje

nekoliko prijatelja koji su ta pisma čitali. Sada smatram da je dobro što su ta pisma objavljena jer

sam svestan da ima mnogo osoba koje pripadaju mlađim generacijala, a o zbivanjima za vreme II

Svetskog rata i odmah posle njega pojma nemaju.

Koristim priliku da Vama, Vašim kolegama i nastavnici izrazim veliku zahvalnost što ste odvojili

dovoljno vremena i imali strpljenja da se upoznate sa zbivanjima tokom II Svetskog rata i mojom

sudbinom.

Autorka : Ana Serafijanović

Moj dragi prijatelju zelim ti jos lepih godina