Hilda Dajč was a young Jewish girl, a student of architecture, who voluntarily went to the Sajmište camp in 1942, where members of the Jewish community were imprisoned at that time. Her testimony - four letters she sent to her friends - represents the words of all the others who were killed alongside her.

Hilda Dajč, before World War II, Jewish Historical Museum.

Hilda Dajč, before World War II, Jewish Historical Museum.

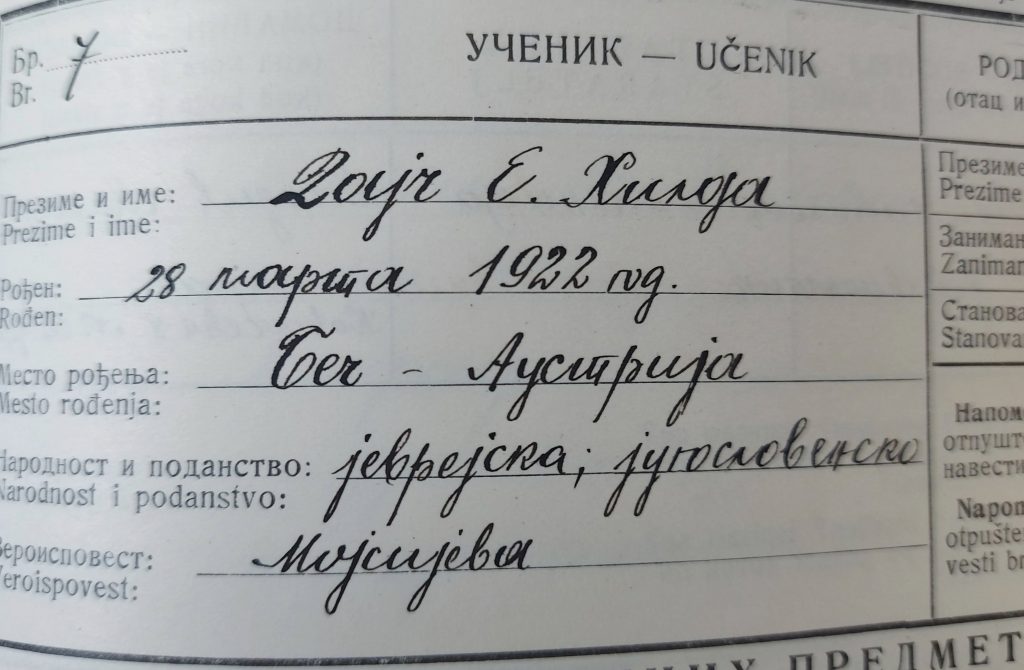

Hilda Dajč was born in 1922 in an Ashkenazi family in Vienna. She soon moved to Belgrade with her younger brother and parents.

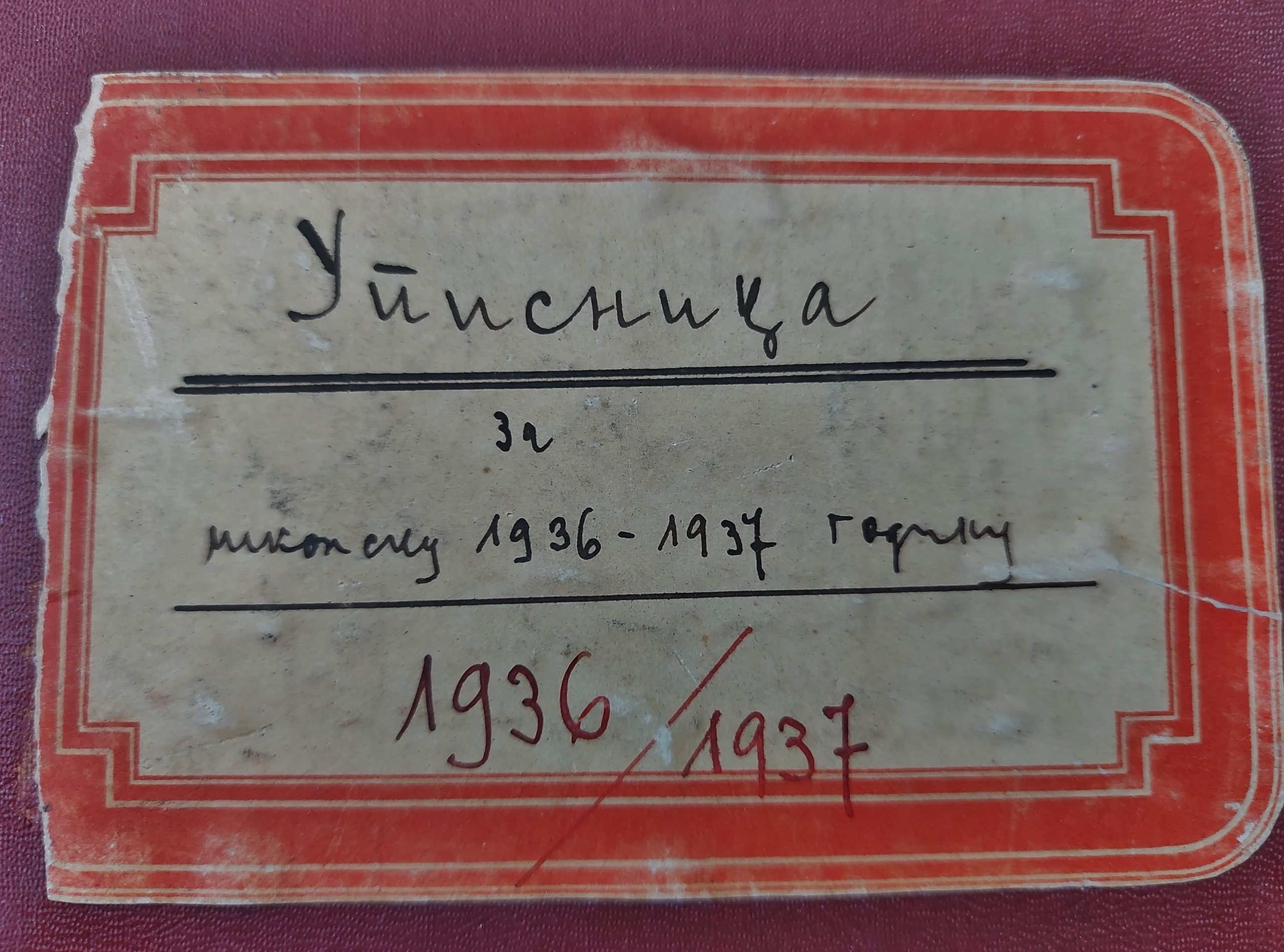

In 1937, she enrolled in the First Women's Real Gymnasium (now the V Belgrade Gymnasium), which was located on Queen Natalija Street at that time.

The former First Women's Real Gymnasium is now the Nikola Tesla Electrotechnical School.

Excerpt from the school records for the student Hilda Dajč."

In April 1941 (with the entry of German troops into Belgrade), the yellow armband with the Star of David became a mandatory identification marker for Jews. The property of Jewish citizens and organizations was destroyed or confiscated. During the summer and autumn, the majority of adult Jewish men were executed, while women and children were taken to the Sajmište camp.

Hilda volunteered to enter the camp as a medical nurse, stating, "There are so many people in need of help, and I must, according to the dictates of my conscience, set aside sentimental attachments to family and home and put myself completely in the service of others."

Like many other stories, this one would have ended there and been lost in time if Hilda had not corresponded with her friends Mirjana Petrović and Nada Novak (Letters I, II, and III are preserved in the Jewish Historical Museum, and Letter IV is in the Historical Archive in Belgrade).

Matična knjiga učenika Ženske gimnazije koju je pohađala Hilda Dajč

In Belgrade, on July 5, 2022, as part of the project by German artist Gunter Demnig, whose work commemorates the victims of the Holocaust, a brass memorial plaque, known as a "stumbling stone" (or "kamen spoticanja" in Serbian), was installed in front of the building located at Maršala Birjuzova Street 9. This memorial plaque is dedicated to the Dajč family, including Hilda Dajč, and serves as a reminder of their presence and the tragic events related to the Holocaust.

The building located at Maršala Birjuzova Street 9 is where the Dajč family lived.

The "stumbling stone" was placed in front of the building where the Dajč family lived.

Hilda Dajč's letters are a testimony to the harsh living conditions and the murders of innocent people in the Sajmište camp. They narrate true events about the deliberate destruction of Jewish and Romani lives during World War II. These letters hold historical, documentary, and humanitarian value, as they highlight the fundamental human need to help people in distress.

Setting up a stumbling stone for the Dajč family

Gunter Demnig, placing the "stumbling stone" in Marsala Birjuzova Street, July 5th, 2022.

First letter

Nada, my dear,

Tomorrow morning I leave for the camp. Nobody's forcing me to go and I'm not waiting to be summoned. I'm volunteering to join the first group that leaves from 23 George Washington Street tomorrow at 9 a.m. My family are against my decision, but I think that you at least will understand me; there are so many people in need of help that my conscience dictates to me that I should ignore any sentimental reasons connected with my home and family for not going and put myself wholly at the service of others. The [Jewish] hospital will remain in the town, and the director has promised that he will take me in again when the hospital moves to the camp. I am calm and composed and convinced that everything is going to turn out all right, perhaps even better than my optimistic expectations. I shall think of you often; you know - or perhaps you don't - what you have meant to me - and will always mean to me. You are my most beautiful memory from that most pleasant period of my life - from the [Literary] Society.

Nada, my dear, I love you very, very much.

Hilda.

7. XII 1941

Second letter

My dear Mirjana,

I'm writing to you from the idyllic surroundings of a cowshed, lying on straw, while above me, instead of the starry sky, stretches the wooden roof construction of Pavilion No. 3. From my gallery (the third), which consists of a layer of planks and holds three of us and on which we each have an 80 cm. wide living space, I am gazing down on this labyrinth, or rather this ant heap of wretched people whose tragedies are as widespread as those who live not because they think that one day things will be better but because they haven't got the strength to end it all. If indeed that is the case.

Mirjana, my dear, your letter is you yourself - I love it as much as I love you. Your words and sentiments are as beautiful as you are yourself and your compassion as great as everything else that is specifically yours. Don't admire someone just because they get things done quickly. Perhaps some people are more altruistic and less energetic and have more humility than ambition; this makes their deeds, however great, pass unnoticed, while the deeds of others are more obvious because they have been performed quickly and resolutely.

Dear Mirjana, there are now 2,000 women and children here, including nearly a hundred babies for whom we can't boil any milk as there's no fuel and you can imagine what the temperature is towards the top of the pavilion with the Kosheva wind blowing as hard as it does. I'm reading Heine and that does me good, even though the latrine is half a kilometre away and fifteen of us go at the same time, and even though by four o'clock we've only been given a bit of cabbage which has obviously been boiled in water, and even though I have only a little straw to lie on, and there are children everywhere and the light is on all night, and even though they shout 'idiotische Saubande' [stupid bunch of pigs] and so on all the time, and even though they keep on having roll calls and anyone missing these is 'severely punished'. There are walls everywhere. Today I started to work in the surgery, which consists of a table with a few bottles and some gauze, behind which there is just one doctor, one pharmacist and me. There's a lot to do, believe me - with women fainting and goodness knows what else. But in most cases they put up with it all more than heroically. There are very rarely any tears. Especially among the young people. The only thing I really miss is the possibility of washing myself adequately. Another 2,500 people are due to arrive and we only have two wash-basins, meaning two taps. Things will gradually sort themselves out - I have no doubt about that. The hospital will be in another pavilion. They frequently count us, and for the same reason the pavilions are surrounded by barbed wire. I don't regret coming here at all - in fact I'm very satisfied with my decision. If every couple of days I can do as much as I've done these first two, then the whole thing will begin to have some point. I know, in fact I'm absolutely convinced, that all this will pass (which doesn't exclude the possibility that it will last several months) and that it will all end well, and I feel good about this in advance. Every day I meet lots of new people and gain new experience - I get to know people as they really are (there are very few here who put on an act). Many of them are taken in as some sort of 'commanding officers'. Even though I would be up to this, it isn't for me - my ambitions don't point in that direction. My dear Mirjana, you'll still be able to recognize me - I won't change - it is only now that I realize from my presence of mind that I am strong enough not to let external things affect me. All I want is for my parents to be spared all this.

I looked up at your window, my dear, when the truck was driving us to the Exhibition Hall, but I didn't see you. Next time we meet we must make up for everything we haven't done together over this year. Who knows, maybe our separation is so unusual…[illegible]…that I'll discover how much I love you and how attached I am to you, even though I haven't been with you all that often.

My dear Mirjana, stay just as you are - you're a darling and I love you so much,

your Hilda

9. XII 1941

Third letter

Nada, my sweet,

The way in which I received your letter was hardly romantic; we two nurses together with a pharmacist had organized making tea with milk (providing the women had brought these with them, because nothing can be sent here, neither do any parcels arrive at all) on twelve spirit stoves - and while we were making it, to the loudest din imaginable both inside and out, tears were running down my face because of the smoke and the paraffin and these were joined by the real, sincere and soothing tears that came from reading your letter.

Here it's so - I don't know how to describe it - it's quite simply a huge cowshed for 5,000 people or more, without walls, without barriers - everyone sharing the same quarters. I described the details of this magic castle to Mirjana and I really don't feel like repeating them. We get either breakfast or supper accompanied by the most abusive of words - on top of that, one's appetite passes and one's no longer hungry. Over the past five days we've had cabbage four times. Otherwise, everything's wonderful. Especially as far as our neighbours are concerned - the Gypsy camp. Today I went there to shave and grease the heads of fifteen people with lice. However, although after this my arms were burning up to the elbows from the cresol, my work is in vain, because as soon as I finish the second group, the first have got lice again.

The running of the camp is in the hands of people from Banat and is based on favouritism or rather 'loverism', but we Belgraders are too docile and they take advantage of this, because as soon as one of them chats with a girl, she becomes his girlfriend. Every hundred inmates have a group commander, usually some whipper-snapper aged between 16 and 20, and up to now they've already picked 100 camp policewomen from the girls aged from 16 to 23. I kept myself well-hidden, because I'm only too aware of my particular attitude towards police of any kind. What their criteria are when they make their choice, only they know.

It's now half-past ten, I'm lying down - I can feel the straw under me (a wonderful substance, especially when it's full of fleas) - and I'm writing to you. I'm very pleased that I've been here from the very start - one experiences so many interesting and unrepeatable things that it would have been a shame to have missed any of them. Even though there are only two taps between the lot of us, I manage to keep clean as I get up before five and go to wash myself all over. Here we have to queue for everything. It's very good of them to try our patience like this. It would be great if everyone eventually got to the front of the queue. That's not so easy. Today they took all the children (boys) - and grown-ups who were with us because they were ill - off somewhere, we don't know where - but of course monotony would disturb our already jittery nerves. You can imagine how much noise 5,000 people make, shut up in one big room - during the day you can't hear yourself speak and at night you have a free concert consisting of children crying, people snoring and coughing and all sorts of other sounds. My work lasts from six-thirty in the morning until eight-thirty in the evening - even longer today - but things will get sorted out as soon as the hospital arrives and that should be any day now. The hospital courier comes here every day, and today it was Hans and I heard from him the bad news that my family will be arriving tomorrow. A weekend like this one is far from ideal, especially for my parents and Hans, who needs a healthy diet. They took all our money and valuables apart from 100 dinars each. The only thing they don't economize on is the lighting - it's on all night and prevents me from having a good night's sleep. My ambitions always have to be satisfied, because I always want everything to be in the superlative. And this is no exception. Ever since I've been here I've been very calm, I've worked hard and with great enthusiasm and have experienced a real transformation. When I was 'free' I couldn't get the camp out of my mind, and now, over the past five days I've got so used to it that I don't think about it at all - instead I think about much more beautiful things, like - you know already that I think a lot about you. In the evening I read. Even though we were only allowed to bring as much as they said we could bring, I've got 'Werther', Heine, Pascal, Montaigne as well as English and Hebrew text-books. Rather a small library, but I think it will serve me very well.

My Nada, I'm not writing all this simply because I want to, but because of a very strong conviction: that we will see each other soon. I've no intention of spending the summer here, and I hope that they (with a capital T) will take my intentions into consideration. I expect their decision soon.

My Nada, I must get some sleep now, I'll be getting up early tomorrow and I must keep up my strength. Bye-bye, my dearest - I'm hesitant about thinking about you in this filthy cowshed so as not to spoil the pure devotion for you I carry inside me.

Affectionate greetings to you, Mother, Jasna and everyone else, from a very happy volunteer.

Fourth letter

My dear,

I could never have imagined that our meeting, even though I was expecting it, would arouse in me such a flurry of emotion and create even more unrest in my already frenzied soul which simply won't calm down. All philosophizing ends at the barbed-wire fence, and reality, which, far away on the other side you can't even imagine or else you would howl with pain, faces one in its totality. That reality is unsurpassable, our immense misery; every phrase describing the strength of the soul is dispersed by tears of hunger and cold; all hope of leaving here soon disappears before the monotonous perspective of passive existence which, whatever you compare it with, bears no resemblance to life. It is not even life's irony. It is its profoundest tragedy. We are able to keep going, not because we're strong, but because we are simply not conscious all the time of the eternal misery that surrounds us - everything that makes up our life.

We have been here for almost nine weeks and I am still quite literate - I can still think a little. Every evening, without exception, I read your and Nada's letters and this is the only moment when I am something else, not just a Lagerinsasse [German for female camp intern]. Hard labour is golden compared with this - we don't know why - on what charge - we've been convicted, nor how long we'll be here. Everything in the world is wonderful, even the most miserable existence outside the camp, while this is the incarnation of every evil that exists. We are all becoming evil because we're starving - we're all becoming cynical and count everyone else's mouthfuls - everyone is desperate - but in spite of this, no one kills anyone because we're all just a bunch of animals that I despise. I hate every single one of us because we've all fallen as low as we can go.

We are so near the outside world, yet so far from everyone. We have no contact with anyone; the life of every individual out there carries on as usual, as if half a kilometre away a slaughterhouse containing six thousand innocent people doesn't exist. Both you and we are equal in our cowardice. Enough of everything!

Even so, I'm not the anti-hero you might think I am from what I'm saying. I put up with everything that's happening to me calmly and painlessly. But the people around me. That's what upsets me. It's the people that get on my nerves. Not the hunger that makes you weep, not the cold that freezes the water in your glass and the blood in your veins, nor the stench of the latrines, nor the Kosheva wind - nothing is so repulsive as the crowd of people who deserve to be pitied, but who you are unable to help and can do nothing else than put yourself above them and despise them. Why do all these people talk about nothing else other than what is offending their bellies and all the other organs of their so highly esteemed cadavers. A propos, a couple of days ago we were laying out the dead bodies - there were 27 of them - in the Turkish pavilion, right at the front. I don't find anything repulsive anymore, not even my filthy work. Everything would be possible if only we could know what can never be known - when the gates of compassion will be opened. What do they intend to do with us? We are in a continual state of tension: are they going to shoot us, blow us up, transport us to Poland…? All that is of secondary importance! We just have to get through the present, which is not pleasant in the least - not in the least.

It's now half-past two, I've been on duty in the surgery all night (every fourth night), in the pavilion they're coughing in unison and you can hear the patter of rain on the roof. Here in the surgery the stove is smoking like hell, but, as the saying goes: who doesn't inhale the smoke, isn't warmed by the fire.

This is my most exciting day in the camp. To want something so much and then to get it is more than happiness [this is a reference to the meeting with Mirjana at the inn across the river from the camp]. Perhaps one day we'll get out of here alive into a happier life, because that's what we all desperately, but by now rather anaemically, want. Mirjana, my dear, we are imprisoned slaves, in fact even lower than that - we're not so much wretched as a despised and starving horde, and when from this position one sees a little of life - meaning you - then one senses so many of life's juices that flow through it. Only - yes that eternal only - to wrench oneself away from that life afterwards is so painful and bitter that not even the sea of tears that one sheds can express it. I cry and they all start laughing: How can you, who conducts yourself like a man, allow yourself to cry like a sentimental teenager?!

But what can I do when in the depths of my heart everything is so horrible. That's the refrain I repeat to myself all night. I know there's no hope of our getting out soon, and outside are you and Nada, all that binds me to Belgrade which, by some incomprehensible contradiction, I deeply hate and deeply love at one and the same time. You don't know, just as I didn't know, what it's like to be here. I hope you will never find out. Way back when I was a child I was afraid they would bury me alive. And now this is some sort of vision of death. Will there be some sort of resurrection? I've never thought so much about the two of you as I do now. I continually talk with you and yearn to see you, because to me you are that 'paradise lost'.

Love from your camp inmate

Written by Iva Pešić